- Home

- Belinda, Lyons-Lee

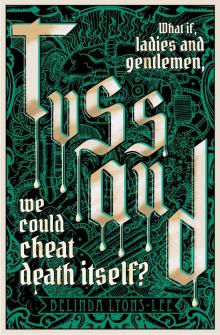

Tussaud Page 7

Tussaud Read online

Page 7

‘You have managed this affair admirably,’ she said, and dipped her head. ‘But do you not think we should try to construct one of these … automatons first before you travel to London?’

‘I have neither the time nor opportunity. I need to purchase all the required parts, and the minute I start sourcing materials, Pinetti’s spies will find me. I need to have the show ready for the London season.’

‘It will be the best time for the show to run, yes. But if you miss it this year, there is always —’

‘It will not do. I must have my show ready this season.’

‘I see. Then it strikes me as odd, monsieur, that you did not consult me before you stole the plans. Why were you so confident I would acquiesce?’

‘Because you have played small long enough, madame. The true artiste cannot ever give up their art. If they do, they can go …’ He let the pause stretch out. ‘Mad.’ The word fell between them. She did not reply. ‘Plans first or you first, it would make no difference. Only that I wanted to strike Pinetti before he found a reason to strike at me first. It is a sort of … game that we play.’

‘I am concerned about the danger I will face if I enter this game. What if Pinetti finds out about our partnership?’

Would Philidor take the bait? He would have to think he had thought of the idea.

She continued, ‘And you are under considerable pressure to be ready for the London season. I would do all that I could from Paris, monsieur, but I fear it may not be enough.’

‘It would be easier and safer for you, madame, if we worked together in the same space,’ he said thoughtfully. ‘But I cannot stay in Paris.’

She sighed with regret. ‘And I wonder further, once this wax automaton is created, who will care for it?’

‘I’m sure it will need to be dressed and such – details hardly worth considering now. What about … What about if you come to London, then, and share my lodgings? We could work there without anyone bothering us, and then you stay on as part of the show. I can find another job for you to do backstage.’

‘Monsieur, what an idea! But then … I do not know that I wish to leave Paris. Although I suspect I will need to see the mechanics for myself, measure them myself, weigh them, feel them, do my own calculations in order to make the perfect wax skin the first time around. Under such time constraints, it would only be prudent.’

‘Yes, yes! Come with me to London, madame. Consider it arranged.’ He seemed quite pleased. ‘I must let you know, I have found premises for the show that will suit us – the Lyceum Theatre.’

‘I do not know it. How many will it hold?’

‘Only a limited number. I want an intimate setting. It is the exclusivity that will bring in the money.’

‘Indeed, once something is seen by the commoner it becomes … vulgar. If I understand you correctly, the aim is for you to – for us to appeal to the wealthy, even the royal.’

‘You understand me perfectly.’

‘But, monsieur, you cannot expect me to pack up all my belongings and travel to London without some sort of advance. For a partnership, it is only reasonable.’

‘I suppose it is. Although this is not quite how I expected it to eventuate. If you agree, I will give you a sum now to cover expenses, and we will negotiate the remaining rate once we are established. I will cover the initial outlay for your materials, your travel, and the renting of our lodgings and food. But once the show has begun, we will come to some sort of … arrangement that will suit us both.’ When she nodded, he smiled and said, ‘I plan to leave tomorrow. When can you meet me in London?’

‘Short notice indeed. But, as it happens, the timing suits me well enough, I can follow soon after. Although I have much to accomplish.’ She smoothed her skirts down. ‘You mentioned lodgings?’

‘I have made enquires with a woman called Druce, who lives in a three-storey terrace on the ground floor at Baker Street. She rents out the first and second floors above her, offering plenty of space. The building is next to a bazaar run by a gentleman who is hardly ever there, apparently, and will not concern us. Does that sound suitable?’

‘Quite. And are we to pretend to be … married?’

‘That may suit our purposes.’

She paused. Should she pretend she needed time to consider this breach of propriety? Allow time for him to be nervous she may not agree? She allowed another moment to pass before saying gravely, ‘This is quite an undertaking, monsieur, especially considering we have known each other for only half an hour, an hour at most.’

‘It is only natural you have misgivings. But I give you my word that I will look after you and protect your interests in this venture. I am not like other gentlemen, madame, who see the female sex as weak and foolish. I applaud your talent, your intellect and your skills, and upon my honour I will do what I can to foster them alongside my own.’

‘Your word? It is just that, exactly that, monsieur – a word.’

Marie was smaller than him, her frame compact and fine; he could use his voice and stature to intimidate her if he chose. ‘If a man does not have his word, he has nothing. This must be enough.’ His tone was indeed reassuring.

‘For the time being it must be,’ she replied, staring up at him. He was a potential threat physically but she wondered, for all his cunning and planning, if she may be more artful than him in reality.

He appraised her old dress before digging into his pocket and handing her some coins. ‘Take these as the first instalment and a show of good faith. Purchase some new dresses, and whatever you need to transport your materials.’

‘Thank you, monsieur.’ She took the money without hesitation.

As planned, he had offered her a way out, and she would climb over more than dead bodies to get to it.

CHAPTER TEN

Marie

THE BRUISED HEADS of the wilted lavender stalks sagged in her memory, heavy with the stench of death. She’d made posies to push against her nose as she picked through the bodies after the executions, and then the flower heads had fallen off or been snapped off by her nervous fingers. Lavender. In pots in the courtyard of Curtius’s house in her younger years, in a bush by the front steps of the terraced townhouse opposite hers now. What once had been the smell of childhood bore upon it the memory of mutilation, even this night.

When she woke up the following morning, she lay in bed much longer than necessary. In fact she’d been lying there awake for nigh on ten hours, the shutters open and the smell of lavender pouring through the window. She needed to decide from the outset the nature of this whole affair. Would Philidor be a business partner, lover, partner in crime? A decision needed to be made today before it all properly began. He had asked her to trust him, but he did not know what he asked. Trust a man, and one who made his money with illusion and trickery? And yet … She must trust him enough to leave here and go with him. And perhaps he would prove her natural caution wrong. What a relief that would be, to have a man actually be true to his word!

She’d known that yesterday would bring about a change in her fortune: she’d slept with one of her blood-stained handkerchiefs under her pillow the previous night. Over the past few weeks a feeling had been growing in her that something was afoot in the other realm that would intersect with her own path. She’d been ready for change – willing it, actually – and she had let the Fates know about this by leaving the handkerchief as a sign.

And voila. She knew who Philidor was, of course. She may have been somewhat reclusive, but she was not without her eyes or her memory of his voice. Or her senses, at least most of the time. He was a stage magician controversial amongst respectable people because of his practice as a purported necromancer. Various incidents had been related in the Le Moniteur that titillated the public interest and provided further fanning of sensation’s flames: the infamous occult demonstration that had resulted in his imprisonment during the Revolution. And he had thought a slight alteration of letters in his name meant a change of identity. Ha

. What was all that to her?

She knew he was a charlatan, him and his supposed golden voice. They all were, but it was of no consequence. He suited her purpose by providing her with the opportunity to escape, earn money again, enough to start her own show and build a new life. And send for Joseph and François. Philidor’s plan was ambitious, yet she didn’t mind that.

With such an opportunity to occupy her thoughts, she noticed that her visions were being pushed to the outskirts of her mind, and she could think more clearly. Calmly. Rationally. She did not find Philidor attractive, and he had not the subtle cleverness needed to be an equal business partner that she could conspire with; his arrogance and pride were a weakness. For now she would make a show of trust and go to London, and she would tolerate him while he made the practical arrangements and they began preparations for the show. But depending on his conduct …

She dug up the palest floorboard in the room, bleached almost white from the sun, and retrieved her stash of notes. She had lived frugally for many years in anticipation of such an unexpected occasion. This morning she would need to be fitted for dresses, as well as to buy some personal items; she would spend the remainder of the day packing, and tomorrow take possession of the dresses then board the cutter from Calais to Dover before travelling by carriage to meet Philidor in Baker Street. It would pain her to leave her collection of heads, the beginnings of her Chamber of Horrors. But for now they must be locked up and left alone, presided over by the guillotine.

This plan felt as though it was enough to keep her visions away. They had come on her soon after she’d been freed, at first as nightmares that woke her with a body so wet it was as if she’d soiled herself. She came to fear going to sleep, where she might again live through the prison and all its horrors. After weeks of sleep disturbances that stretched her nerves to snapping, the visions crept over the fence of nocturnal hours and began playing in the fields of daylight. Some small part of her knew, even in the midst of it all, that what she was seeing, hearing and smelling wasn’t real. But what was real, what was imagined? Perhaps these memories of her capture had become part of her bodily composition, stored alongside her internal organs in their own wet, dark place.

As she washed herself, she savoured the touch of a bar of soap that had been triple milled, wrapped in brown paper and placed in her bedchamber drawer many seasons ago. Then, taking a large pair of scissors usually reserved for her creations’ hair, she stood in front of the mirror and cut her own, untouched in over ten years – ever since it had been shorn in preparation for her execution. She left it to sit just below the shoulders, so that she could still pin it up and wear a headpiece for extra length and body if required. Then she retrieved a simple day gown that still hung in the back of the cupboard, shook it out and placed it by the open window for the breeze and sun to banish the mustiness.

She breathed deeply of the lavender as if challenging it to confront her directly, now that she was awake and a course of action determined. Yes, she would go with this Philidor. She would treat him as an acquaintance with a shared interest, for now. But she would remain on her guard. Just who was the greater performer remained to be seen.

At the dressmaker’s shop, Marie studied her own reflection and saw clearly what Philidor had only hinted at: she had aged. Her hair was now strewn with grey where once it had been black, but a dye would remedy that. Her cheeks were less plump than they had been; a few weeks of eating well again would hopefully restore some shape. And her skin was still in beautiful condition – no harsh sun had touched it for many years, so that the faint blue of the veins below her eyes was visible. Yes, if nothing else, solitude had been beneficial for her skin, and now she needed only to fatten herself up, colour her hair, buy some dresses, and she would blend back in with society.

The dressmaker took her measurements in silence, and Marie was definite about what fabric she wanted. A fawning sort of woman, the dressmaker assured Marie that ‘her girls’ would work on the dresses overnight and deliver them tomorrow – for a higher price, as was only reasonable.

Marie had forgotten how much was expected in interactions with the public: the exchange of pleasantries, the eye contact, smiles and dipping of heads, and if one gesture was wrong or ill-timed it was noted and remarked upon. That had been tiring with the dressmaker, milliner, grocer and apothecarist. Marie was relieved to return home and slide the bolt over the door. But she had a new parfum, boxed and wrapped up tight in her arms, as well as a fresh piece of meat and some potatoes to cook a proper meal.

As she prepared the meat, peeled the potatoes and sliced the handful of greens, her mouth watered in anticipation. How quickly her senses had returned after being dulled with dust and isolation for so long.

She ate at the square table in the kitchen, having polished a knife and fork on the threadbare drying cloth. She even poured herself a glass of wine from a bottle found amongst the gloom of her cellar. She was attempting to civilise herself, and she found that the little rituals brought enjoyment.

After she’d washed up, aware now of the pleasant weight in her stomach, she opened the workshop door to survey her collection, standing there for a full minute. What should she take with her? Certainly she would need her tools, but she could buy the clay, plaster, wax and the rest of the materials in London. What about the heads themselves? Her eyes rested on Marie Antoinette. Philidor, the simpleton, thought she could make this figure before the London season started, but that would be impossible in the time available. Why make a new head for this escapade when Antoinette’s head was undeniably perfect? Antoinette and Marie had been through too much together to be parted, not now that Marie was on the brink of a new venture that could, if she was clever, actually centre around Antoinette. But she would keep this idea to herself and see what transpired with him once settled in their lodgings. She remembered Philidor’s vain attempt to stifle his interest when he’d first laid eyes upon the Queen. Yes, Antoinette would accompany Marie to London. Marie touched Antoinette’s soft hair and ran her fingertip over her closed eyelids. ‘I would never leave you,’ she said, and almost believed Antoinette’s eyes opened in reply. But of course they didn’t. That would have been the thought of a madwoman.

She put the notebook aside to pack in her bag later, then collected her tools and rolled them in a sheet of paint-spattered canvas tied with brown twine. She gently lifted Antoinette’s head from the marble pedestal, lowered it into a sturdy hatbox, covered it with a square of soft linen then packed it tightly with scrunched newspapers. She did the same with the death mask of Antoinette. The two boxes sat side by side; she would carry them as hand luggage so they remained in her sight and care for the duration of the trip.

Once in London, Marie sent her luggage ahead to Baker Street while she paused to visit Gunter’s, a confectioners with a tearoom on the side that she’d seen fleetingly from the carriage window. It seemed that in London women were not customarily welcomed into such establishments, but in Gunter’s their presence was perfectly acceptable. She needed refreshment and a moment to steady herself for the next encounter. Gunter’s cakes, pastries, biscuits and candied fruits were a feast for the eyes with their pretty colours and lavish coats of sugar. The tearoom would be the perfect place for her to frequent while she stayed at Baker Street, a respite from Philidor when needed.

The set of rooms in the narrow-terraced lodgings above Baker Street were presided over by the landlady Druce, who had a red, round face and a bosom that extended beyond the shapely to the grotesque. She appeared to see the latter as an asset, making space for her breasts to jiggle like a bowl of custard. Marie detested her on sight.

‘Your luggage is already here,’ the landlady said, upon opening the front door to Marie. ‘Wasn’t sure where you wanted it, so just put it on the first floor.’

Marie nodded as she stepped into the entrance way.

‘You’ve plenty of room up ’ere to be sure.’ Druce began to puff up the staircase ahead of Marie. Her posterior, with i

ts layers of soiled skirts, filled the stairwell while a limb of some child poked out from underneath an armpit.

Marie frowned.

‘And your husband … he is …?’ Druce enquired, pausing at the top of the stairs, hand on the doorknob.

‘An artiste,’ said Marie, not bothering to correct the assumption.

‘As am I.’

‘Oh, he’s ever so polite, your husband is. And handsome too, if you don’t mind me saying so.’ Druce winked at Marie and pushed her breasts up further.

‘I do. And he chose these lodgings because you assured him we would be undisturbed.’

‘Oh yes, ma’am, I’m not the interfering type, if you know what I mean. Not like some landladies I know of, always watching and listening to see what their lodgers are up to. No, I’ve got me hands full with my baby.’

‘Quite,’ said Marie, not bothering to look at the aforementioned sniveller, whose pink scabbed chin was shiny with drool. ‘And it’s “madame”, not “ma’am”. My husband and I will not have any need of additional services and must not, under any circumstances, be called upon.’

‘Oh, I do beg your pardon. Madame. My mistake – and yes, I see, you want to do your own meals and laundry then. Well, I’m sure that’s not the usual arrangement with my lodgers, but whatever you say, madame. Oh! Pardon me, here I am talking away, and we’ve not even got inside.’ She opened the door and stepped back, allowing Marie to pass through into the parlour.

Marie crossed over the threshold and smelt the fug of alcohol in the air surrounding Druce. This went some way towards explaining the ruddy cheeks.

‘After you, madame.’ The woman’s eyes shifted around Marie’s profile in return. ‘What sort of art do you do, if you don’t mind me asking?’

‘I do mind,’ said Marie again, with a sniff. She turned to look down upon the woman and realised her oily scalp radiated a peculiar smell. ‘You have been paid handsomely for your rooms and little else need concern you.’

Tussaud

Tussaud