- Home

- Belinda, Lyons-Lee

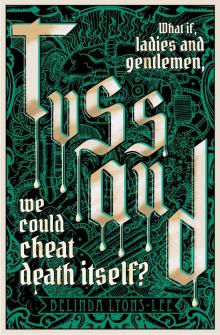

Tussaud Page 8

Tussaud Read online

Page 8

Marie appraised the first floor, noting the sitting room, scullery and two smaller bedchambers, then toured upstairs to the remaining two bedchambers and further large room that could be used as her workshop. All the rooms were tired and old and the furniture close to ruin but they would be serviceable, for the time being.

‘I have seen enough and wish to get settled,’ she said upon returning to Druce, who stood waiting like a steaming farmyard animal. ‘You may go.’

‘Yes, ma’am. Here are the keys, a set for you and one for your husband.’ Druce placed them on a peeling side table just inside the door.

‘And the other?’ asked Marie.

‘What other?’

‘I assume you have a spare set?’

‘I … ah, upon my word it’s common practice, if you lock yourself out I —’

‘That will not be the case, I can assure you. I will relieve you of the spare set.’

‘Well, I don’t know about that.’

‘If you wish to receive the full amount offered for this hole when my husband is already paying you twice what it’s worth, you will surrender the keys.’

Druce bounced the now squalling baby furiously on her hip, and Marie noticed each drop of spit as it sprayed in the air. ‘I’ll get them from below and bring them up directly.’

‘Leave them by the door.’

‘Yes, madame.’ Druce departed, smacking the child’s wrist from its mouth as she went.

‘Oh, and one more thing – this side table,’ said Marie, pointing to where it sat in the parlour by the door, ‘when was it brought up?’ ‘Been here for years,’ Druce snapped, half turned in the doorway.

‘Was it the first thing brought into the room?’

The landlady blanched. ‘I’m sure I don’t know, I … such a question, I’m sure I don’t know and —’

‘Good afternoon.’ Marie dismissed Druce with a wave of her hand, shut the door and listened to her thump back to her ground- floor quarters.

After pushing two dishevelled armchairs out of the way, Marie sat down on one of her trunks to look out the large parlour window at Baker Street. According to superstition, if a table was brought in as the first piece of furniture to a room then it brought good luck. She reached for the blood-stained handkerchief in her corset, rubbing her thumb and forefinger in its folds; thankfully its luck was strong enough. This room was eye level with the buildings opposite – offices, from the looks of them, with shops at ground level. Marie had decided Philidor could have this, the first floor, and she would take the second. She needed the most light and the least disturbance if she was to create.

It was summer and the rooms were ripe with the smell of unwashed Englishmen. The English style was appalling; they had no natural sense of elegance or how to make the most of one’s features. She wrinkled her nose. The window ledge, in her mind’s eye, was covered with other people’s dried skin, their crumbs, their dust and their hair. It all needed thorough cleaning, something Druce had clearly not attended to. Instead of looking out at the carriages and people bustling below, Marie trained her eyes on her own reflection. Even though the pane was smeared with the residue of some dirty cloth, poorly used, she could still see that her appearance remained unsoiled after her travels. She was pleased with the dresses and even more so with the parfum she’d dabbed at her wrists and neck. She would show these English ladies what style was – she could still turn a head, even at forty. And although she had no intention of initiating any liaisons, it was satisfying to have the surreptitious glances come her way again, even on the cutter over here.

Footsteps on the wooden stairs: a helpful signal. She would never be taken by surprise. It was Druce leaving the key, and her heavy tread back down suggested she was none too happy about it. Pah. She was a stupid woman whose craven mind was filled only with money to spend on drink and the like.

Another minute in solitude, then, to gaze down below and watch the street sweepers solicit coins. But no, Marie was not permitted to savour this. Another carriage drew up level with the front door.

Philidor.

She watched him alight, then saw the driver haul out his trunks and Philidor look up to the window where she sat. She drew back immediately. For a moment she’d forgotten all about this man and his grand plans. She’d allowed herself to think this place was hers, that she could be alone with her trunk and dresses and parfum, and watch the street’s entertainment. But no, this all came with conditions.

She opened the door as the stairs creaked under the driver’s weight, the trunk slung across his back. He hefted past her, grunting as he did so. She held her breath; the English were clumsy and awkward, while a Frenchman would have carried it without mimicking an animal.

Philidor swept off his hat and bowed. ‘Madame Tussaud. How lovely to see you.’

‘A pleasure, to be sure.’ She extended her hand, then heard a step creak on the ground floor with the weight of a foot, the landlady’s neck inching along behind it. ‘Husband,’ Marie said, raising her voice, ‘come inside. You must be tired.’

Philidor smiled, then paid the driver with a few coins and stepped over the threshold into their quarters. But Madame Tussaud was already there.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

Philidor

HE HAD ESCAPED Paris apparently without Pinetti and his spies being any the wiser, although to be sure would be arrogant. Pinetti had plenty of coin to spend on informants and disguises, and possessed an uncanny way of knowing what Philidor was up to.

He had been staying at Brooks the gentlemen’s club in St James that had been his home on previous occasions he’d visited London. Brooks was comprised of three storeys of yellow brick influenced by the European style of architecture and provided aristocratic gentlemen with an array of rooms in which to while away their time. Familiar, comfortable surroundings and the company of true Englishmen had assisted him with blending in with local conversation, habits and style. The recent wars had made many of the English suspicious of foreigners, particularly the French, but nothing that his golden tone, impeccable manners and dress couldn’t smooth over.

Dr Gribble, a physician at Bethlem Asylum, had become a particular friend of his at the club. His recommendations – such as where to dine outside the club and the best tailor, along with a fine establishment for entertainment in the Strand – had all been most helpful. They had much in common.

The club was close to the Bank of London, where Philidor had attended a pressing appointment earlier. With his trunk now packed and waiting in the carriage, he had one visit to make at the Strand before arriving at his new lodgings at Baker Street.

He knocked on the door of a respectable-looking three-storey terrace, the façades of each one in the long row painted white. The door was opened as usual by a man. Tall. Broad. Long, lank hair. An overbite. Philidor had been thankful that before his first visit Gribble had warned him about this man but still, many visits later, the fact was he still found the Collector’s presence unsettling. Philidor said Gribble’s name and was granted admittance to the hallway, where, as was his usual practice, he signed the bill before being permitted further into the depths of the house.

The madam bustled around him in the drawing room, although it wasn’t an ordinary drawing room. It was filled with half-naked ladies, and between them sat gentlemen like himself, in various states of arousal and intoxication. This was the first stage: see what was on display, what was offered, what could be bought. To gain access even to this room came at a price. One had to know the right name.

Philidor’s favourite was already occupied, the madam said.

Would he like a drink and perhaps to make the acquaintance of another lady while he waited? Yes, he would, he replied curtly.

The madam handed him his whisky. She knew him by name, and he decided to thank Gribble again when he next saw him at the club.

But he was incensed that his favourite wasn’t ready for him – she damn well should have been. She was his. But no, he rebuked himsel

f as he sipped his drink and met the eyes of a redhead with especially plump breasts. His favourite was probably many men’s favourite. The redhead plucked at her right nipple while still holding his gaze.

He felt something else besides desire: another pair of eyes on him.

He looked around. The Collector. When not answering the front door, he stood just inside the drawing-room door, never drinking, smoking or smiling, just watching. Protecting the ladies.

He was called the Collector, Gribble had said, because he collected money or bodies, and he didn’t mind which. Those patrons rich, respected or well-connected enough were permitted to use the services of the establishment under obligation; the madam kept a running collation of services rendered and stipulated a date for payment. Philidor was one of the fortunate gentlemen granted such terms. Today’s visit had gone on his bill, given the recent expenditures he had needed to make on his show. But it was of no consequence – there would be plenty of coin crossing his palm after opening night.

The Collector’s eyes left Philidor’s and roamed the room. He was shrewd, that man. Made it seem like you were a nobody to him, but he branded each face into his memory, of that Philidor was certain.

The redhead approached. He took another sip of his drink. Her hand was on his knee; she was leaning over him, her nipples hanging deliciously close.

‘I have been waiting for you,’ said a voice, and the redhead pulled back as if stung.

Warm, soft arms encircled his neck from behind. It was his favourite. She had come for him, and he was ready.

When he arrived at his new lodgings at Baker Street sometime later, Marie stood on the threshold of their rooms. She was there first. Perhaps he shouldn’t have dallied at his previous engagement. This oversight felt, in some intangible way, like it had now put him at a disadvantage with Madame Tussaud. Troubling to have such a feeling. Marie welcomed him inside and called him ‘husband’, more for the listening ears of the Druce woman than anything else. Once the door was shut, Marie then retreated upstairs without comment; she had clearly claimed the upper rooms as hers. He could hear her short steps across the floorboards from the trunk to the wardrobe. This was why he should have been here first. She was an intriguing creature, improved in appearance from the woman who had greeted him at her door days ago. Her face had seemed to fill out, her hair now black and glossy, her eyes clear, her dress perfection and a scent on her of self-assurance. He pinched the tip of his moustache between his fingers, his annoyance draining away as he considered another possibility. Could this relationship move from business to liaison? No, it would not do to complicate affairs. Plenty of ladies in the Strand were compliant without attachments – although the cost was putting him in debt.

But Marie had seized the second floor when it was to be his. Its bedchamber was by far the superior, and its other rooms boasted the biggest windows with the most light, the most privacy and the best view. His annoyance rose again, this situation needed to be addressed.

‘Forgive me, madame, but I fear there has been some misunderstanding,’ he began, as he reached the top of the stairs and knocked on her bedchamber door, which stood ajar.

She turned. ‘Yes?’

‘It seems there has been some confusion regarding the arrange- ments. I was to have this floor, and you were to have the first-floor rooms.’

‘I see,’ she said, in such a tone that implied otherwise.

‘I’m sorry to bother you when you have begun to unpack, and I’ll help you move your trunk.’

‘You will do no such thing. These rooms please me, and I need space to work.’

‘As do I. And so I thought that —’

‘What you thought was not correct. And the decision was not made in consultation with me. I require full light, as much as this weak English sun can give, in order to get the precise tone of the skin, monsieur, you understand?’

Philidor’s jaw muscles closed down hard. ‘I also require the light to see the pieces of the clockwork, madame. It is most intricate working with tweezers and screws the size of a splinter. I am a master of my craft, I will be working long hours, and I need the right conditions to create.’

‘As do I.’ She looked at him steadily. ‘And so we are at an impasse.’ Her trunk was half unpacked, two dresses hung in the wardrobe, glass bottles of perfume, powder and trinkets already sat on the top of the dressing table, and the bed was filled with silk garments of pink, green and cream. The room smelt of a woman, alive, sensual, and he was disarmed. ‘Of course you can have these rooms,’ he heard himself saying. ‘I will buy more candles and oil lamps for my workshop. It will suffice.’

‘That is good.’ She picked up a fetching green silk dress, shook it out and folded the hanger within. He had been dismissed. ‘And do not visit this floor again unless I invite you,’ she added, her words addressed to his back as he departed. ‘I am unsettled by sudden noises and intrusions, and if I am to create this … this automaton for you, I do not wish to be disturbed.’

‘What about dining?’ he said.

‘I am accustomed to a sparse diet. However, I intend on breakfasting each morning at Gunter’s Tea Shop down the road. If I wish for anything more, I shall see to it myself.’

He retreated downstairs and sat in one of the two armchairs by the bay window. His leg knocked against the rough-edged table at knee height. He tipped his head back and smelt the residue of the previous tenant’s oil on the worn fabric on the cushion. The woman was trying his patience, but she was a creative genius. And she would make him enormously wealthy. He would keep all the accounts, which was only proper; she had no way of knowing how much they would earn once the show was underway. He would pay her something that would satisfy and keep the remainder. She was not his equal in intellect, so it stood to reason that she did not deserve to earn his equal in coin. Besides that, he had debts to pay.

Philidor realised in the morning that he would have to heat his own water to wash in, and this displeased him greatly. Was it worth paying Druce extra to help with the domestic duties? No, not yet. He had no money to spare. After using cold water instead, he dressed and went to sit in the parlour window. What he didn’t expect was to find Marie already there, dressed, hair styled, face composed, and seated in the rickety armchair opposite his with the legs that looked like twigs. ‘Good morning, monsieur, did you sleep well?’

‘Tolerably. And you?’

‘Yes, surprisingly. I find I always sleep better upstairs. Now, while I understand you have your own business to attend to today, I require money to purchase my materials. Here is my list.’

He read it, noting the compact handwriting and the itemised products. He looked up to find her watching him. ‘This is preposterous,’ he said. ‘Plaster, clay, wax, buckets and troughs? To buy all of these things, in these quantities – well, the cost is considerable.’

‘Which is why to commit to making a wax figure is not to be entered into lightly. It will cost as much as that in coin, and it will cost me about three hundred and fifty hours of my life, monsieur.’

‘Three hundred and fifty?’ He put down the list. ‘So that would be … what, two weeks at least if you were to work unceasingly.’

‘Which is inconceivable. The head alone will take me four to six weeks.’

‘But that’s … that’s preposterous! I need it done within a month.

All of it. I’ve already booked the theatre and —’

‘That will result in inferior work. I will not put my name to something so poor.’

‘I have paid for you to be here to do the work. You will produce it, madame, according to the period of time I desire.’

Her eyes narrowed. ‘The only way that I can meet your demand is if I use an existing head. And I will not do that.’

‘Why didn’t you think of that earlier?’

‘Why didn’t you say what you wanted earlier, instead of telling me now?’

‘I wanted to design the head myself, madame. I wanted a half- deformed thing

that would send them into conniptions when it moved.’

‘I can do that. But it will take time.’

He cursed as he stood, pulling the curtain open further than was necessary, which tore the thin fabric. ‘I told you we were to be ready for the season, madame. Perhaps you did not understand me.’

‘Perhaps you have brought the date forward with the arrange- ments for this theatre, which is two weeks earlier than the official start of the season. You have given no thought for —’

‘I will lose my deposit,’ he said curtly. ‘This is all your fault.

You should have thought to bring a head with you.’

‘Actually, I did. But I do not wish to use her.’

‘Who?’ He turned from the window to glare at her.

‘Antoinette. But she is special, I cannot have her pawned over like —’

‘But she’s perfect!’ he cried, then reined himself in. ‘She is not without her charms.’

‘I do not want to use her.’

‘The only way we will be ready for the performance on the dates I’ve booked will be if we use her. If we keep on schedule I won’t lose the deposit. I’m afraid we have no choice.’

‘I have a choice.’

‘Not if you want to stay in this venture. I will not see it fail because of your stubbornness.’

Marie paused. Was it possible she had contrived to let him think he had the advantage now? She made a face as if defeated. ‘Very well, I will use her,’ she said. ‘But I want to be paid an additional amount, as the risk I am taking with my most valued possession is high. And the hours already painstakingly exerted to replicate her from the death mask are too many to count. I will have to carve open the back of her head, as well as open the eye cavities. It is … complicated.’

‘Yes, yes, I will pay you extra then,’ he said, throwing up his hands. ‘Now go on with your business, while I get on with mine. Here’s the money to buy what you need.’ He pulled a clutch of coins from his pocket and counted them out. ‘The first limbs of the mechanical skeleton will be ready in a few days’ time … if I’m not interrupted further.’

Tussaud

Tussaud