- Home

- Belinda, Lyons-Lee

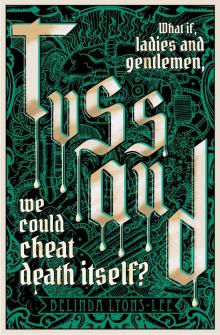

Tussaud Page 9

Tussaud Read online

Page 9

She took the money with lowered eyes. What had happened to the madwoman he’d met at her front door? He nodded and picked up the newspaper. A short silence. A breath. Why was she was still here? He lowered the paper.

‘What is that?’ She pointed through his ajar bedchamber door.

‘My bedchamber is private, madame.’

‘Your shoes. They appear to be on the bedside table, monsieur.’

‘They don’t appear to be, they are. What of it?’

‘Why?’

‘They need to be taken out to be polished after I finish reading,’ he said, twitching the paper back open. ‘And what business is it of yours where I place my shoes? It is my bedchamber after all, cramped as it is.’

‘It is my business when your laziness and ignorance bring bad luck down on this household.’ She pushed through his door to snatch his shoes and place them on the floor.

He stood up. ‘Control yourself, madame. Such a breach of privacy and etiquette is improper.’

But the woman’s face was tight, and the madness appeared in her eyes once more. ‘It is not for you to question me or the ways of Fate,’ she said. ‘But you, with your arrogance, have just brought a bad omen upon the both of us. Even the peasants are more educated than you in the ways of the world.’

She left the room, and he tugged at the curtain, which had slunk closed on its rotting wooden rings. The fabric disintegrated into a scrap that he kicked away in disgust. Not much longer now before he could leave this hovel and live, permanently, in the conditions he deserved. As for Tussaud, he would continue to outlay the money, a small investment that promised an extraordinary return. What he hadn’t bargained for was an equal business partner. In a woman.

First he wedged a chair under the doorhandle to be sure it could not be opened. Although propriety dictated that she wouldn’t barge in uninvited, she had proven she was not trustworthy in this regard.

He looked at the array of parts laid out before him. He’d had to get another table, making three, moved into this cavern that had optimistically been called a room. Pinetti’s drawings – only for an occasional reference, mind you – were propped up against a stack of books. Philidor needed them as a reference but that fact annoyed him no end. It was as if, even now, the ink whispered to him of the superior intellect of Pinetti contained within its open pages.

The wires were a thicket of metal stalks, alongside a proliferation of wooden cast-offs, varying in sizes. The most important piece, the one that would take the most time to make, was the round wooden disc called the cam. The shape and size of the indentations that lined the perimeter determined all the automaton’s movements; if the wood was smooth, the movement would be fluid, but many teeth in succession would make gestures jerky, as the lever that attached to the cam was forced to oscillate quickly up and down over it. The cam functioned as the mechanical memory of the automaton and so needed to be crafted with precision and care lest the surface be too rough or the distance between each mark too little or too much. But more than one cam was needed for the series of intricate movements that Antoinette would need to perform. A whole stack would be required, perhaps fifty or so, each with a hole in the middle skewered through with a brass rod which would then all be lodged within the torso.

In separate piles were the screws, nails, springs, cogs, nuts, bolts, gears, hinges, pins and chains that he would add, piece by piece, to the scaffolding in order to replicate joints, allow for movement and hold together the wooden skeleton.

He had two glass bottles filled with oil, a small brush and shovel, balls of twine to hold pieces together, and a heap of rags with which to polish and wipe each part. On the other table was an assembly of saws, a lathe, chisels, files, hammers, screwdrivers, clamps, planes and sandpaper, as well as tweezers, tongs and pliers. His mind raced ahead, assembling each part before him so that he saw, already complete, a copper skull sitting atop the spine of a metal and wooden creature, more alien than human. It brought to mind the first automaton he had ever seen, at the age of ten.

1780

Württemberg, Hegau (modern day Germany)

He and Pinetti followed their father onto the grounds of the estate, the biggest one just outside their village. They had been allowed, for the very first time, to accompany him as he delivered the meat ordered for the consumption of the Baron and Baroness von Rassler. The aristocrats were putting on a feast this evening, a private party at which there was to be a curiosity. According to the rumours of the other village boys, it was a tiger, a mermaid or a man who swallowed knives. All sounded equally thrilling to Philidor, yet Pinetti did nothing but complain as they walked over. ‘My shoes are getting muddy.’ ‘The air is too cold.’ ‘Why must I walk?’ Pinetti never did like physical exertion, preferring to stay at home with their mother, warm, sleek and lazy like a cat by the fire.

Their father just ignored his protestations, always more patient with his oldest son than youngest.

‘Think of it like an adventure, and we can finally see the house!’ Philidor said. ‘I’ve waited so long for this.’ For the manor had occupied his thoughts ever since he could remember. He’d dreamt about what lay behind those gates, beyond the rows of trees, only ever seeing the chimneys standing tall above the leaves. It had become for him an imaginary place full of mystery, intrigue and enchantment, a place where anything was possible. And the people who lived there? Such imaginings filled his mind at night as he lay on the straw bed under the table, next to his brother.

And at this moment, for the first and last time, Philidor was proud of their father. The man had an important job; he was a regular visitor to the house, allowed admittance through the gates. And that was something.

‘Look at this, Pinetti!’ Philidor crowed, running ahead. ‘Imagine it, will you? Imagine it’s ours! We live here!’

Their father turned around, waited for him to catch up, then smacked him hard across his face. ‘Keep your voice down and stop behaving like a fool.’

Pinetti sniggered while Philidor’s cheeks flamed with shame.

‘You’re an idiot,’ said Pinetti, after their father had again picked up the handles of the cart and strode ahead of them. ‘You will never live in a place like this. This is only for the rich and the clever.’

‘I’m clever,’ Philidor retorted. ‘I can read and I’m learning to write. Faster than you.’

Pinetti laughed. ‘It means nothing. There are other ways of being clever that bring money, not just knowing letters.’

‘Like what?’

Pinetti glanced at their father, who was still ahead of them. ‘Like having the sense to get out of this village, for a start.’

‘Leave the village? And do what?’

‘Anything you want. But you are too small and scared to do anything other than what you are told.’

‘You’re hardly an inch taller than me, and anyway, you talk nonsense. We have no money, we are butcher’s sons!’

‘That’s your first mistake.’ Pinetti turned angry eyes on him. ‘I am not a butcher’s son, little brother. When I’m old enough, I will be whoever I decide to be.’

‘You can’t pretend to be someone you’re not, and that’s wrong in any case, that’s lying.’

‘All I need is a chance,’ said Pinetti, as the grand house came into view. ‘Just one chance and I’ll take it. And one day something like this will be mine.’

‘What an idea! We can live in it and share —’

‘Find your own dream.’ Pinetti scowled as he put his fists into his pockets.

Their father swung around to the rear of the house, and they followed, crossing the courtyard to the back door. ‘Stay here,’ he said, before knocking and being granted admittance by the dour- faced cook.

As soon as the door closed behind them, Pinetti moved.

‘Where are you going?’ said Philidor, taking a step after him. ‘Father said to stay here.’

‘So stay here, then.’

Philidor was not going to wait w

hile his older brother went off to explore: he could discover the mermaid or the tiger without him. Their father would be some time inside, he was sure. It was safe; they were together.

Pinetti snuck along the side of the house with Philidor behind him. They turned the corner and saw the casement window ajar. Pinetti stuck his head inside. Philidor stepped into the flowerbed and stood beside him on tiptoe, nudging the window further open. It took a moment for his eyes to adjust so he could see inside the room. There was a small table in front of the window, side on, facing a row of seats set out for an audience.

‘What is it?’ said Philidor. His shoulders jostled against Pinetti’s, his feet stomping further on the flowerbed.

‘Nothing but a stupid toy. Wish I could see the ladies’ bed- chambers.’ Pinetti moved on to the next window.

Philidor returned to the sight before him. What a strange contraption this curiosity was! He leant further in and stopped. He heard a noise, a squeak, then a wheeze like the tightening lungs of an old man in his death throes. Philidor’s sight sharpened: a diminutive figure, like a porcelain doll, sat on the table, the white lace ruff around its neck now taking shape in the gloom. The figure was a little boy, mounted on a pedestal and sitting behind a miniature wooden desk. His right hand held a goose feather quill, and in front of him lay a piece of blank parchment. The open window illuminated the doll’s fine porcelain cheeks and black horsehair eyelashes. Philidor heard the sound again, an oily wheeze, then the boy’s quill lifted, hovered over the glass pot of ink, submerged the tip then returned to the page and began writing.

Was it magic? Was it a trick? Was it … demonic? The nib scratched as the boy breathed again, and then, almost with a sigh, raised his hand to signal completion before closing his eyes. Philidor tried to read the scrawl sideways but couldn’t. A quick glance behind him, then he pulled himself up onto the window ledge and leant further in alongside the doll to see the word: Betrayal.

A voice from behind him. Strong hands clasped his feet and pulled him roughly out of the window to fall amongst the dirt and flattened flowers. The voice growled, ‘What the devil do you think you’re doing?’ His father.

Philidor looked around. Pinetti was nowhere to be seen.

By the time they returned home that night, his father was a boiling mass of rage that declared itself in broken red veins on both cheeks. Baroness von Rassler had also found out about the spy, thanks to the cook who had heard Pinetti’s tale when he’d burst into the kitchen saying Philidor had run away from him; the baroness had insisted on Philidor being thrashed if she was to continue employing their father, as well as deducting from his bill the amount owing to cover the damage to her precious flowerbed. Philidor knew what was to come and wanted to run back into the encroaching night to escape. But what was out there was worse than what was in here.

While his mother tried to talk her husband away from the belt he was undoing in the kitchen, Philidor confronted his brother in the stairwell. ‘Why did you go?’

‘Why do you think, silly?’

‘You betrayed me.’

‘I have to gain favour when I can.’

‘So you decided to tattle on me in order to gain it?’ Philidor said, as he heard his father’s footsteps pace around the table while his mother’s plaintive voice rose.

‘You’re the competition, you imbecile. Of course I have to, I told you this morning that I’m clever. But you better think of something – he’s in a real fit tonight.’

‘I can’t think,’ Philidor hissed. ‘I’m scared.’

‘You’ve always been too slow,’ said Pinetti, and smiled.

Philidor’s heart gave a heavy throb inside his chest.

Pinetti whispered, ‘If I were you, I’d run.’

And Philidor did. But not before his father had broken his nose.

The various metals glinted dully in the candlelight, throwing washes of rusty orange, red and yellow hues across the room. The piles appeared as if they had been dropped from the bowels of some monstrous beast that had shaken free of its afflictions. They reminded him of the real rubbish he’d been forced to sift through, gather and sleep amongst when he had run away that night. Those first few nights on the streets had been unforgiving and made him think of his own bed – if one could call a sack of straw under the kitchen table a bed – with something akin to fondness. The warmth of his brother’s body next to his own had kept him from freezing, while on the street he had nothing but the icy grip from the cobblestones through his pile of newspapers in a corner of a forgotten alley. Nothing could stop that deep, deep cold that rose up from some hellish place and seeped into the very bones of a man, or a boy.

Even still he didn’t return home; he didn’t hobble up to the front door and plead with his father to be let in. It was pride, he now knew, and although he couldn’t put a name to it at the time, he recognised it as a certain degree of stubbornness that would not let his father lay a hand on him again. Ever. This resolution, coupled with the imagined sneer on his brother’s face, warmed him through the bitter nights when his feet were so cold they shrunk inside his worn woollen socks and refused to cooperate regardless of how many times he stood to stamp them.

That’s when he began walking and met a group of vagabonds who took him in. They were a dirty, dishevelled lot, each travelling with the group for their own reasons and loyal only if it suited but it didn’t concern him. Their rough exterior hid their quick wits and inventive tricks with sleight of hand that left Philidor in awe, night after night as they sat by the fire.

And so began his life on the road, and in the wagons, and in the ramshackle tents that drew in the people of each town who yearned for the colour, the noise and the sensations they brought – as well as the pots, pans, tonics and herbs each of them respectively sold – like exotic fruit being offered up for all. His natural ability, honed over years of ducking, weaving and avoiding angry hands, aided him as he kept company with the older boys, some of whom also didn’t mind a bit of petty thievery on the side. Not enough to be noticed, mind, just a little here and there so that deft fingers caught a lost wallet or bracelet whose clasp had unfortunately broken. All such common occurrences anyway that hardly anyone remarked upon it – if they did, it was put down to carelessness on behalf of the owner. The next town would provide the opportunity to sell the goods on, and the labourer would reap the benefits.

At work on the automaton, Philidor picked up a tiny silver screw and rolled it between his thumb and forefinger, feeling the ridges of the spiral that would provide the traction when ground into the adjoining piece.

He’d always had a knack for using his hands, although it wasn’t until he’d started singing that he realised his voice was his greatest asset. He had been taught all manner of things by some of the more skilled travellers, those who had been on the road for a while. He was a child back then and eagerly learnt all that could be taught, in exchange for singing for his keep and being allowed to travel with the company. Every time his part in the performance came, and he stood before the firelight in second-hand cast-offs that were miles too big for him, the teasing would stop, and he felt the power of holding an audience spellbound with nothing but his voice. No tricks required.

Still, he hungered for more, and this had driven him into a town one afternoon, a few years later, when he should have been resting for the night’s performance. They were back in Württemberg, the town of his childhood, and he had a fancy to see his home. He imagined knocking at the door, his brother answering, all pale and skinny, bruises around his eyes, and their mother’s mouth open at the return of her prodigal son. He would regale them with tales of his adventures, show them some tricks and gloat that he was no longer bound by his father – or scared of him. What if his father was home? No matter, he would be an old man, his frame sunken with age and drink. Yes, Philidor was free from the cage, and his life was wonderful! He would grind this fact into the desperate eyes of his brother so that Pinetti knew who the victor was. Philidor had

got the better of him and risen up above his allotment in life. And, he had a few coins to spend. They jiggled pleasantly in his pocket as he walked, visions of buns and pastries dancing before him, and perhaps a jug of ale before he paid a visit to the house.

But then opportunity came knocking.

He crossed the bridge, dallied as he considered coming back in the morning to try for some fish in his old spot, then rounded the bend of the narrow street and came upon a scene of utter chaos from which he instantly decided he could benefit.

A carriage, a swell one at that, had overturned, spilling its contents as well as passengers over the road. Two horses lay on their sides screeching in a manner ghastly to even the most hardened heart. Shopkeepers – the milliner, blacksmith and baker, by the look of them – had all rushed to help the humans and the horses, and the bystanders who had previously been shopping and gossiping were also sucked into the whirlpool of catastrophe.

Pulling his cap a little lower over his eyes, Philidor slipped in amongst the carnage of chests and cases that had been jolted open upon hitting the ground. He picked up a lovely silver watch with some very nice engravings, as well as a new pair of gentlemen’s black trousers and a pair of boots.

He was just quietly helping himself to a shirt when a hand clamped down on his shoulder. ‘Stop, thief!’ a voice cried. Throughout the crowd, angry eyebrows turned upon him, and fists closed in readiness to strike.

Philidor looked into the face of the gentleman who had caught him. A gleaming moustache, narrowed dark eyes, pale skin and hair slicked back. And a stench of pomade about him that overrode the manure in the street.

It was his brother, grand in his suit, hat and walking stick.

Tussaud

Tussaud